Hello Visitors!

Below are a few writings that describe my past work as well as my current research.

I am currently living and working in Morris, Minnesota where I teach in the art department.The use of digital technology in my work began around 2015, as I was awarded a Jerome Fellow Award. It was then I began to utilize 3D laser scanning and the cnc router to produce work. As of Spring 2021,I am still experimenting with 2D and 3D digital technology and I have become much more interested in what I can achieve on the surface of a piece while merging this technology with traditional building materials and techniques.

Current Project: In the Spring of 2020, I was awarded a $27000 Grant In Aid from the University of Minnesota. I was scheduled to travel to Japan in October 2020 to begin research on a new body of work while on a single semester leave. A brief description of the research to be done in Japan: With a laser scanner, I will "extract" shapes from traditional Japanese architecture. I will then merge these files with details often found in American vernacular architecture that I have also scanned into a 3D modeling program. This will result in small to medium scale bronze assemblages that will include wooden structures. Due to restrictions related to the 2020 pandemic, I spent the Summer and Fall of 2020 in my studio with a different focus than the aforementioned work related to my recently received grant. I used this time to focus on color and pattern,this resulted in 6 new small to medium-scale works, a few of which were shown in my most recent exhibition at Bing Davis Memorial Gallery at UIU In Fayette, Iowa. I will re-schedule my trip to Japan once travel restrictions are lifted. I am excited about this new direction in my work and my color and pattern studies are ongoing, with 3-4 new pieces scheduled to be finished by June 2021.

Jason Ramey:

The Personal Ecology of

Furnishings and Walls

By Michelle Grabner

“It is never we who affirm or deny something of a thing; it is

the thing itself that affirms or denies something of itself in us.”

-Baruch Spinoza

Sculptor Jason Ramey admirably stakes out and navigates a psychological landscape taut with existential metaphors and personal narratives. At the same time, he unflinchingly confronts the problematic historical debates between the visual arts and crafts, furniture and props, display and architecture by employing the tropes of these dichotomies in his work. When one experiences Ramey’s work, his acknowledgement of the ill-defined space between art, craft, and design practice is not immediately apparent. That is his intention. What’s primary is his uncanny ability to stretch vernacular signifiers, through formal and material intervention, into intimate emotional stages. His heavy use of found objects suggests that his work is contoured by storytelling, memories and industrious objectives. His human-scaled spaces delineate small domestic theaters and pop-up tragicomedy plays. Yet Ramey deftly imbues his work with a spectrum of critical thinking, embracing modernist functionalism and narrative drive while simultaneously disrupting distinctions between high and low, fragmentation and autonomy, originality and authorship.

Noted historian and theorist Glenn Adamson has built a career out of mapping craft’s power structures, locating its authority in the economic and political manifestations of the language. Identifying craft’s cultural influence as well as articulating its limitations is important work. It is work that Ramey intellectually commits himself. Yet the political underpinnings of craft are peripheral to his practice. His core theme is place- a familiar and domesticated place where a viewer can identify the conditions that shape humanity. For Ramey, it is not only the production of craft that humanizes but also the literal representation of space and body.

Drawing on personal narrative Ramey says in his artist statement that” growing up, I was often curious about who might have constructed the walls in my family home, and what type of people they were.” Were they like me? Are they still alive? “These walls weren’t just inane parts of my childhood home, they were my childhood.” Memory is bound up in the space that enfolds our material world- the people, the furniture; the crown molding are props and markers. Ramey’s statement contemplating the original builder of his childhood home elegantly fuses Ramey as artist, as builder, and as questioner. “I wondered this because these walls were keeping me safe, and I had no idea who put them there.” Who were [those people] and why did they build these walls for us?” Such musings reflect a profound emotional attachment to domesticated space, and that is what Ramey infuses in the spaces with his wall-and-furniture constructions.

Ramey’s spaces without enclosure are still intimate and private. His open-form constructions integrate only one or two domestic elements, a sparseness that refutes public exchange. The walls are confident in their delicate role protecting private space; they embrace and even engulf the surrogate furnishings that also conspire to create a reflective and psychologically charged domestic domain.

The following is an essay by Jane Blocker. Dr. Jane Blocker is a specialist in contemporary art and critical theory and currently teaches in the Art History department at The U of M Minneapolis.

Uncanny: Jason Ramey

“This unheimlich [unhomely/uncanny] place, however, is the entrance to the former Heim [home] of all human beings, to the place where each one of us lived once upon a time and in the beginning.”

Sigmund Freud

“By means of the light in that far-off house, the house sees, keeps vigil, vigilantly waits. …Through its light alone, the house becomes human.”

Gaston Bachelard

We might think of poor Alice, drinking her potion and eating her cake so that she monstrously stretches up and shrinks back down, but the house itself is also enchanted. It too expands and contracts in surprising ways. Despite its coziness and intimacy, it is a place in which one “experience[s] what is large in what is small.” French philosopher Gaston Bachelard, in his famous book The Poetics of Space, goes so far as to describe the house as a cosmos or universe. No matter its actual size or opulence, the home into which one is born constitutes the known world and impresses on the child mind a sense of enormity, which is why, when we return to such spaces as adults, we marvel at how small they seem. Every giant chair the child once struggled to occupy, every formidable stair he fought to climb, has been miniaturized. From cellar to attic, the house rises up vertically, toweringly in our imaginations and memories, but at the same time, Bachelard suggests, it “appeals to our consciousness of centrality.” Its corners, cupboards, niches, closets, and drawers may be measured with the small ruler of intimacy, privacy, and protection. For Bachelard, its tendency to grow and shrink makes the home especially suited to memory, fantasy, and daydreams.

Sigmund Freud argues that the home is a trigger for the uncanny. The home or heimlich (home-like) is, in his view, a redoubling of the womb, the first space we inhabit as living beings. Freud identifies it with the maternal, with whatever is “familiar and old-established in the mind,” and thus with longing and nostalgia. The uncanny or unheimlich, despite the “un” by which it announces itself, is not the opposite of the home, but is rather “that class of the frightening which leads back to what is known of old and long familiar.” The uncanny is often a double (the doll or mannequin in place of the human; the house in place of the womb), which first appears commonplace, perhaps tinged softly with memory, but which soon fills us with dread. It is utterly alien. “The Heimlich is a word the meaning of which develops in the direction of ambivalence,” Freud remarks, “until it finally coincides with its opposite unheimlich. Unheimlich is in some way or other a sub-species of heimlich.”

Ambivalence abounds in Jason Ramey’s sculptural installations, where miniature and gigantic, memory and fantasy, home and uncanny come together at right angles to form so many conceptual corners. The odd conjoining of disparate elements is a common tendency in Ramey’s work, such as his Queen Anne and Lath (2011), in which a found Queen Anne style chest, painted in a “joyful-sad” robin’s egg blue, morphs into and forms a corner with a lath wall. For Bachelard, “every corner in a house, every angle in a room, every inch of secluded space in which we like to hide, or withdraw into ourselves, is a symbol of solitude for the imagination; that is to say, it is the germ of a room, or of a house.” Something extraordinary happens in that place, that angle, where cabinet and wall meet, which we might name enchantment. Something is inaugurated in that touching, as if by a magic wand, which Bachelard explains by saying, “The corner is the chamber of being.” Reflecting on the house where he grew up, Ramey echoes the philosopher, remarking that, “These walls weren’t just inane parts of my childhood home, they were my childhood.”

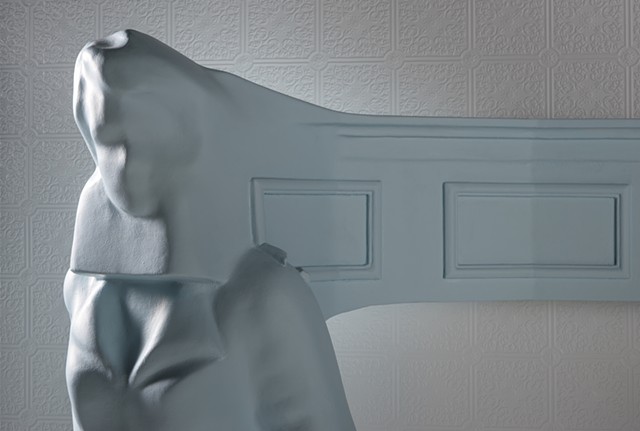

In Mantel (2015) he has used a 3-D printer to enlarge a found tiny plastic figurine meant for a model train village or architectural model. Like Alice, she has grown unexpectedly into a life size doll. She is a blank or placeholder in monochrome robin’s egg blue. Originally made of molded plastic, her fingers and eyes, the crease in the sleeve where her shoulder bends, the buttons on her bodice, and the shoes on her feet are all rendered crudely. She poses awkwardly in mid-stride, her right arm akimbo and her hand resting on her hip. She wears a 1950s era dress with a Peter Pan collar, pleated skirt (frozen in mid-sway) and cloth belt, and the clutch purse in her left hand is stuck permanently to her side.

This overgrown figurine is posed in a domestic setting in front of a white wall, the surface of which is embossed in a pattern of squares containing floral motifs, punctuated at the corners by medallions. She is attached at the head and neck to a mantelpiece, which bends away from the wall behind her like a hungry snake reaching out to swallow her up. The mantel, embellished with moldings and applied decoration, recalls a traditional middle class home, yet it seems uncannily to be animated, as though attempting to detach itself from the otherwise familiar mise en scène it serves. Of course the hearth is a well-worn metaphor for home, family, and indeed civilization itself, but it also has uncanny features: it is an odd gaping aperture in the center of the home, a conduit from inside to outside through which only air and smoke pass. Bachelard considers the light emanating from the house, whether from candles, electric lamps, or fireplaces, to make it a corporeal being, warm as living flesh, animated and breathing. It is, as he says, strangely human. Like Rene Magritte’s famous painting Time Transfixed (1938), in which a small train appears to charge from a fireplace into the viewer’s space, Mantel offers an inexplicable, surreal episode that Alice might be tempted to describe as “curiouser and curiouser.”

A second work, Built In #2 (2015), engages more overtly with the corner and meditates more self-reflexively on the sculptor’s practice. Here, in a punning gesture, Ramey takes a miniature figurine of a construction worker or carpenter (perhaps a sculptor?) and scales it up to life size. Like his female companion, this builder has been plucked from a model train enthusiast’s tiny scene. The stereotypical laborer (long sleeves rolled up at the elbow, overalls clipped over the shoulders, a 1930s Depression era cap) crouches down, his left knee bent outward and his right knee on the floor. He reaches down to work on the oak flooring to which he is attached and from which he seems mysteriously to emerge. He faces blankly like the daydreamer into a corner where two half walls meet. “From the depths of his corner,” Bachelard remarks, as though picturing this oddly giant figurine, this man who is an object, “the dreamer remembers all the objects identified with solitude, objects that are memories of solitude and which are betrayed by the mere fact of having been forgotten, abandoned in a corner.”

Although these works seem to juxtapose a number of opposites (animate/inanimate, miniature/gigantic, homely/uncanny, real/imagined, human/furniture), their queasy revelations also involve doublings, repetitions of the same. Take, for example, the wallpaper pattern. Pattern is, like the mold, the trace, the scribe, the stamp, a mechanism for copying, for repeating with greater or lesser degrees of complexity. It is in its again and again-ness, its mundane proliferation of shape and color, where that uncanny feeling begins to overtake the viewer. It is enhanced by the mise en abyme of these works’ self-reflexivity, for they are sculptures that meditate on the practices of sculpture (casting, building, and pressing), works of art that daydream about objects becoming art.

Upcoming Exhibitions

Solo Exhibition Watkins Gallery - Winona State University

Jan 11- Feb 16- 2016

I'm pleased to announce that I am one of 5 recipients of The Jerome Foundation Emerging Artist Grant for 2014/15. In addition to a 12,000 award, I will be exhibiting with the other 4 recipients in an exhibition to be held at The Minneapolis College of Art and Design. More info here http://www.jeromefdn.org

I was recently invited to participate in Emma International Collaboration in July 2014. I will be 1 of 100 artists participating in this event. Emma is held in The Ness Creek arts site near Big River Saskatchewan. For more info on Emma check out their site

http://www.emmacollaboration.com/about.php

Little Forward Gallery, Madison WI 2014

Jason Ramey New Work , Olive Deluce Gallery Maryville MO,

Northwest Missouri State Univeristy, show opens on Jan 27th and is up for one month, solo exhibition - Visiting artist NMSU January 2014

Aesthetic Afterlife, Marquette University Haggerty Museum of Art, Jan 2014 (show extended to August 2014)

Bellevue Arts Museum, Bellevue Washington June 2013-Traveling Group Show

Basille Gallery, Indianapolis Indiana, June 2013

Leigh Yawkey Woodson Museum of Art, Wausau Wisconsin, April 2013 Solo exhibition in conjunction with Torqued, Bent, and Twisted traveling exhibition

For Immediate Release: June 21, 2012

Contact: Jason Ramey

JASON RAMEY RECEIVES INTERNATIONAL SCULPTURE CENTER'S 2012 OUTSTANDING STUDENT ACHIEVEMENT IN CONTEMPORARY SCULPTURE AWARD

(Hamilton, NJ) Jason Ramey of Madison Wisconsin has been awarded the prestigious International Sculpture Center's Outstanding Student Achievement in Contemporary Sculpture Award for 2012. Jason Ramey is a student at The University of Wisconsin

The International Sculpture Center (ISC) established the annual "Outstanding Student Achievement in Contemporary Sculpture Award" program in 1994 to recognize young sculptors and to encourage their continued commitment to the field. It was also designed to draw attention to the sculpture programs of the participating universities, colleges and art schools. The award program's growing publicity resulted in a record number of participating institutions; including 174 universities, colleges and art school sculpture programs from six countries for a nominated total of 434 students.

A distinguished panel made up of Donna Dennis, Winifred Lutz & Joseph Becherer selected 12 recipients and 22 honorable mentions through a competitive viewing process of the works submitted. The selection of the recipients from a large pool of applicants, including international students, is a great accomplishment and testament to the artistic promise of the student’s work.

The 12 award recipients will participate in the Grounds For Sculpture's Fall/Winter Exhibition, which will be on view from October 20, 2012-April 7, 2013 in Hamilton, New Jersey, adjacent to the ISC headquarters. The artist's work will be featured in the October 2012 issue of the International Sculpture Center's award winning publication, Sculpture magazine as well as on the ISC’s award-winning website at www.sculpture.org.

The International Sculpture Center (ISC) is a member-supported, nonprofit organization founded in 1960 to champion the creation and understanding of sculpture and its unique, vital contribution to society. Members include sculptors, collectors, patrons, architects, developers, journalists, curators, historians, critics, educators, foundries, galleries, and museums-anyone with an interest in and commitment to the field of sculpture. Please visit www.sculpture.org for further details.

###

International Sculpture Center, Publisher of Sculpture magazine, 19 Fairgrounds Rd., Suite B Hamilton, NJ 08619-3450

USA

TEL 609.689.1051 FAX 609.689.1061 www.sculpture.org

I was recently awarded The First Chazen Prize to an Outstanding MFA Student from The Chazen Museum of Art in Madison Wisconsin.

The Chazen Prize is offered by the museum in collaboration with the Art Department; the winner is selected by an outside curator. This year's curator is Michelle Grabner, professor and chair of the Department of Painting and Drawing at the School of the Art institute of Chicago. She is a Wisconsin native and previously taught at the UW for 6 years.

R